Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be. Originally coined in 1688 by a medical student investigating the tendency of Swiss mercenaries to become homesick to the point of physical incapacity, nostalgia soon changed from being a curable physical ailment to being an unassuageable psychological condition, a sickness of the soul.

This shift was the result of nostalgia being partly decoupled from the concept of homesickness. Homesickness can be cured by allowing the sufferer to return home, but nostalgia came to signify a longing not for a particular place but for a by-gone age forever out of reach… short of someone inventing time travel. However, despite becoming de-pathologised, nostalgia never quite managed to shed the negative connotations of its medical origins and the late 20th Century’s decision to turn nostalgia from a condition into a marketing strategy did little for its respectability in certain circles.

By the early 21st Century, nostalgia was a growth industry. Old TV series and films were being re-released on DVD, old sweets were making a come-back; nothing was ever ‘dated’, but everything was ‘traditional’, ‘old school’ or ‘retro’. This obsession with the past was seen as profoundly unhealthy, as it seemed like a retreat from the real world.

Nostalgia expels us from the present while simultaneously encouraging us to draw closer to an idealised past that is simple, pure, beautiful, moral, joyous; a past utterly at odds with a present that is complex, monstrous, tainted, miserable and corrupt. Nostalgia takes our fears and doubts about the world around us and uses them to construct a heavily-censored and largely invented past that can seem so vibrant and clear in our memories that it starts to seem more real than the real world. We are a culture of madeleine munchers. The American poet and critic Susan Stewart once voiced her distaste for nostalgia in these terms:

“The nostalgic dreams of a moment before knowledge and self-consciousness that itself lives on only in the self-consciousness of the nostalgic narrative. Nostalgia is the repetition that mourns the inauthenticity of all repetition.” — On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (1993) pp. 23

Nostalgia is widely seen as a conservative, if not actively reactionary, sentiment: a rejection of the real in favour of a retreat into the imagined, an abdication of our right to re-shape the future in favour of an acceptance of the unyielding tyranny of the traditional, the past and the dead. But what is nostalgia if not a utopian desire? When Plato, Francis Bacon, Thomas More and Karl Marx dreamt up their political utopias, they too were projecting an idealised state onto a time other than the present. They too were writing about worlds that did not exist. They too were yearning for something that was not there. They too were looking beyond the eternal present of the real world.

Far from being a simple desire to rewind the clock, nostalgia is part of a subtle constellation of attitudes towards the past and fictional worlds. Attitudes that can certainly be reactionary but which can also be fiercely progressive and even revolutionary.

Consider, for example, the nostalgia of the Fallout series of games. Ostensibly set in a post-apocalyptic United States, the prelapsarian culture revealed amidst the wreckage of the games’ wastelands is both more technologically advanced than that of contemporary America and more culturally regressive. Fallout‘s Antebellum America is a world of robots and plasma rifles as well as 1950s aesthetics and attitudes. By making the player comb through the ruins in search of better weapons and equipment, the Fallout franchise makes us — as characters in the game — yearn for the material wealth and sophistication of this vanished past while also encouraging us — as players of the game — to laugh at the ridiculous patriotism, sentimentality and arrogance of 1950s Americana. The Fallout franchise is a game in which ironic detachment and nostalgic yearning co-exist in perfect harmony.

This artful cognitive dissonance is beautifully expressed in the Tranquillity Lane mission in Fallout 3 (2008). Tranquillity Lane is an idealised version of a 1950s American community; just how idealised a version is never made clear, but the implication is that even by the standards of the Fallout franchise’s setting, Tranquillity Lane is something of a utopia.

Tranquillity Lane is run as a virtual reality simulation, allowing inhabitants of the vault to live out their days in an ideal community despite the fact that the real world has been reduced to ashes by a terrible nuclear war. However, far from being ideal, Tranquility Lane is actually the site of a nightmarish social experiment run by the vault’s corrupt and insane overseer. In order to free his father, the character is forced to undertake a number of increasingly brutal and immoral tasks in order to paradoxically both ‘fit in’ with the community and escape it. The suggestion that brutality and insanity not only lurk beneath the surface of 1950s suburban bliss actively sustain the fictional ideal displays a similarly subtle layering of nostalgia, irony and political playfulness to that displayed in the opening sequence of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) in which the camera zooms into the immaculately tended lawn to reveal writhing insects and a severed ear.

A similarly complex set of attitudes towards the past can be seen in an independent game by Christine Love called Digital: A Love Story (2010).

Taking only a couple of hours to play through, Digital is set “five minutes into the future of 1988”. Love conjures up this fictionalised 1988 using a number of different strategies, the most obvious of which is the visual.

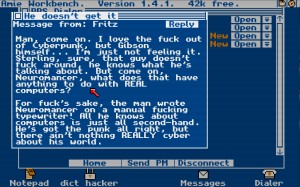

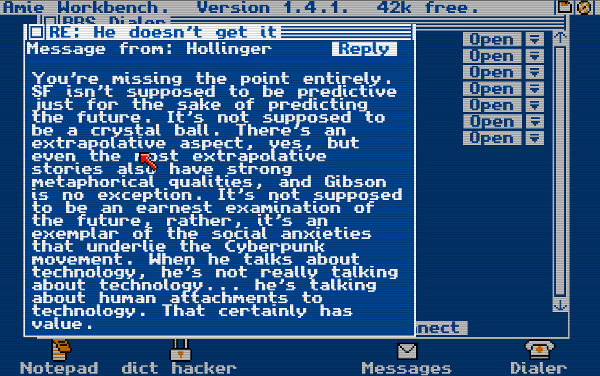

Digital looks and plays very much like a ‘retro’ version of Introversion Software’s hacker simulation Uplink (2001); both games make you experience their world entirely through a computer interface and both games revolve around attempting to gain access to a series of protected networks whilst working your way through a cyberpunk-infused story featuring rogue Artificial Intelligences.

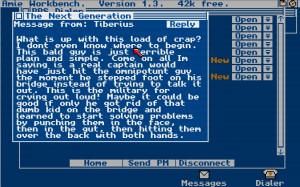

However, while Uplink has you experience the world through a hyper-stylised and uber-slick OS that owes more to cinematic depictions of hacking than it does to real computing, Digital projects you into a lovingly recreated homage to the Workbench operating system native to the Amiga brand of home PCs that were popular in the mid to late 1980s. The eye-watering combination of searing blues, rusty oranges and gigantic red mouse pointers perfectly capture the way in which the Amiga’s aesthetics blended bold new world futurism with the sorts of aesthetic choices you get when you allow computer science nerds to choose your colour schemes. But the aesthetic nostalgia does not end with the visual: Love also treats us to modem sounds and the sort of awful synthesiser muzak that was once wheeled out by devotees as indelible proof of the Amiga’s technical superiority over its commercial adversaries. [I don’t care what you say, my tracker tunes were the bomb, yo. – PGR.] As a recreation of the Amiga-experience, Digital is very nearly perfect but it is precisely in the little mistakes and discrepancies that Digital takes wing as a work of speculative fiction.

Digital takes place amidst the isolated network of BBSs that existed prior to the emergence of the internet. Operating very much like the computer systems portrayed in the film War Games (1983), these servers ran 24 hours a day on isolated phone lines and were accessed by dialling directly into them using your home phone line. In reality little more than dead letter drops for text files and pirated software, Love transforms the BBSs into fore-runners of the USEnet groups and online forums that dominated online discussion prior to the rise of blogs and proprietary social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter. From the point of view of computer culture in the late 1980s, the BBSs in Digital are almost science fictional in their community spirit and ability to connect people, but from the point of view of the game’s audience, they are tools of nostalgia and parody taking us back to a rapidly disappearing recent past in which the internet was a much smaller place than it is today. The world of Digital is a world small enough that one could turn up on a forum, ask to be put into contact with someone you know to be online and reasonably expect people to pass on the message. Everyone is expected to know everyone… even if it is simply as a string of ASCII characters.

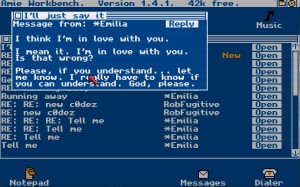

The willingness of early internet users to forge sometimes quite intense relationships with people who were frequently little more than an alias is something that Digital is clearly fascinated with. There was a time when, on the internet, nobody knew you were a dog, but as we have moved towards proprietary closed-loop communication platforms and towards a greater integration of the real world with the online one, it has become harder to maintain online privacy, let alone anonymity.

In his sensational recent book The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2010), the political scientist James C. Scott paints a picture of civilisation as a rising tide of oppression, bringing taxation and corvee labour to upland populations who had previously been free to run their own affairs. Scott argues that, far from welcoming the safety and economic stability of civilisation, many peoples have fled into the hills and taken on ethnic and cultural characteristics designed to keep civilisation at bay.

In his sensational recent book The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (2010), the political scientist James C. Scott paints a picture of civilisation as a rising tide of oppression, bringing taxation and corvee labour to upland populations who had previously been free to run their own affairs. Scott argues that, far from welcoming the safety and economic stability of civilisation, many peoples have fled into the hills and taken on ethnic and cultural characteristics designed to keep civilisation at bay.

Indeed, under this view, the Taliban are not a bunch of backward loonies waiting to be civilised by the Afghan government; rather, they are a collection of people who owe both their political and their religious identities to a conscious rejection of the rule of the Afghan government and their American overlords. Their religious extremism does not prevent them from being good citizens; it is an externalisation of their desire to remain free and unfettered by the trappings of civilisation.

This metaphor also applies to the internet, where scare stories about paedophilia and terrorism have forced those desirous of real online freedom (including the freedom to not be held responsible for anything you say) out of mainstream online communities and into ‘edgier’ communities such as 4Chan, Futaba and 2channel. Due to their dedication to anonymous posting and their tolerance of slander, online bullying, the posting of illegal images and active participation in various criminal activities, these communities are frequently threatened with closure by the authorities in a way that eerily echoes undertakings such as the Inclosure Acts of British history and the recent attempts by the Pakistani army to bring the region of Waziristan under centralised government control.

Look beyond the retro stylings, the dodgy music and the revisitation of old game-play mechanics such as making you scribble down important pieces of information, and you’ll see that Digital: A Love Story is a game that is fiercely nostalgic for the idea of the internet’s lost frontier.

Once upon a time, the internet was seen as a kind of digital Wild West, a wild and woolly frontier just outside of the embrace of civilisation where you were liable to encounter all kinds of things, both pleasurable and horrific: a cultural shatter zone outside of the purview of government. However, just as new settlers brought civilisation to the American West, the popularisation of the internet and its gradual integration into every aspect of our daily lives has brought civilisation to the online world.

By creating a fictionalised past with one foot in the 1980s (when computing was very much a niche hobby) and one foot in the 2000s (when the internet was large enough to start supporting discrete cultural communities), Love is offering us the chance to feel nostalgia not just for the by-gone age of an uncivilised internet but also for a fictionalised frontier where all kinds of technological possibilities seemed only a few inches out of reach. Indeed, if the early internet showed us that it was possible to hate and love a string of ASCII characters, then surely we were only ever a successful Turing test away from falling in love with a rogue AI?

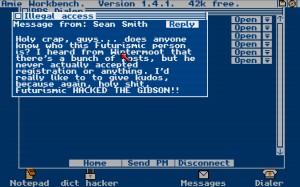

Digital‘s plot deals with the attempt by a young BBS user to regain contact with his online squeeze after the BBS they use to communicate goes down in a mysterious crash. The game’s protagonist tracks his online girlfriend across a number of BBSs, gradually learning the skills of the hacker as he goes. However, as he breaks through new boundaries and “Hacks the Gibson” (a beautifully anachronistic reference to both the 1995 film Hackers and the ‘father’ of cyberpunk William Gibson), the protagonist comes to realise that the string of ASCII characters he has fallen in love with is just that… a string of characters… a computer programme.

Digital‘s plot deals with the attempt by a young BBS user to regain contact with his online squeeze after the BBS they use to communicate goes down in a mysterious crash. The game’s protagonist tracks his online girlfriend across a number of BBSs, gradually learning the skills of the hacker as he goes. However, as he breaks through new boundaries and “Hacks the Gibson” (a beautifully anachronistic reference to both the 1995 film Hackers and the ‘father’ of cyberpunk William Gibson), the protagonist comes to realise that the string of ASCII characters he has fallen in love with is just that… a string of characters… a computer programme.

At the end of the game, Digital‘s protagonist predictably gets his girl, thereby reinforcing the nostalgic vision of an uncivilised internet frontier in which even the lowliest of nerds could battle the odds and win the heart of a beautiful computer. However, Christine Love is not in the business of peddling happy endings; Digital‘s emotional arc is far more than a simple romance.

Despite being a game that consists mostly of sending emails, Digital never allows you to see the emails you send or to compose any of your own. If you want to communicate with other BBS users, you click ‘Send PM’ and the game does the work for you immediately prompting a PMed response with what information or flavour text the game decides to give you. However, because you only ever see one side of the game’s conversations, you only ever experience the game’s human elements from a distance. This means that when the game’s protagonist falls in love, the experience of love simply never filters through to you as a player. You simply do not care about the fate of the rogue AI. The emotional void at the heart of Digital is a stroke of genius. Far from undermining the game’s engagement with the possibilities of a non-existent past and a non-existent internet frontier, the hollowness cuts through the nostalgic fog with a strong dose of irony. The message of Digital is that the past was never as pretty as we would like to think, and any warm-fuzziness we might feel from retreating into a fictional past is necessarily hollow… because it is not real.

Despite being a game that consists mostly of sending emails, Digital never allows you to see the emails you send or to compose any of your own. If you want to communicate with other BBS users, you click ‘Send PM’ and the game does the work for you immediately prompting a PMed response with what information or flavour text the game decides to give you. However, because you only ever see one side of the game’s conversations, you only ever experience the game’s human elements from a distance. This means that when the game’s protagonist falls in love, the experience of love simply never filters through to you as a player. You simply do not care about the fate of the rogue AI. The emotional void at the heart of Digital is a stroke of genius. Far from undermining the game’s engagement with the possibilities of a non-existent past and a non-existent internet frontier, the hollowness cuts through the nostalgic fog with a strong dose of irony. The message of Digital is that the past was never as pretty as we would like to think, and any warm-fuzziness we might feel from retreating into a fictional past is necessarily hollow… because it is not real.

Christine Love’s Digital: A Love Story is beautifully constructed and powerfully argued reminder of the complexity of our visions of the past. Far from being a simple case of ‘past = good’, ‘future = bad’, nostalgia can be used as a tool of social satire and criticism: a tool which allows us to acknowledge that, while it is okay to yearn for a non-existent past, we live in the present… and make our lives in the future.

###

Jonathan McCalmont is a recovering academic with a background in philosophy and political science. He lives in London, UK where he teaches and writes about books and films for a number of different venues. Like Howard Beale in Network, he is as mad as hell and he’s not going to take this any more.

Jonathan McCalmont is a recovering academic with a background in philosophy and political science. He lives in London, UK where he teaches and writes about books and films for a number of different venues. Like Howard Beale in Network, he is as mad as hell and he’s not going to take this any more.

Jonathan recently launched Fruitless Recursion – “an online journal devoted to discussing works of criticism and non-fiction relating to the SF, Fantasy and Horror genres.” If you liked the column above, you’ll love it.

[ The fractal in the Blasphemous Geometries header image is a public domain image lifted from Zyzstar. ]

“[Taliban] religious extremism does not prevent them from being good citizens; it is an externalisation of their desire to remain free and unfettered by the trappings of civilisation.”

This comment seems to me extremely short-sighted. Not long ago they bore not just the trappings of civilization but also its authority and oppressed others with it. And they seek that same authority again.

“No, no, it’s OK, it’s fine; my nostalgia is ironic!”

Ciro — The civilisation of the Afghan plains is weak and barely capable of mimicking the trappings of the modern-day nation state. When civilisation recedes, the barbarians come. Same as with the Romans.

As for the Taliban seeking the legitimacy and authority of the state, I’m not so sure. If you poke at a hornet’s nest with a stick and the hornets come pouring out you would be foolish to assume that the hornets are inherently hostile to you. They are hostile to being poked. The Pakistanis, under American pressure, have decided to force civilisation upon their uplands just as the Burmese generals tried to force ‘civilisation’ upon their hinterland.

Pretty interesting article, except…

“However, because you only ever see one side of the game’s conversations, you only ever experience the game’s human elements from a distance. This means that when the game’s protagonist falls in love, the experience of love simply never filters through to you as a player. You simply do not care about the fate of the rogue AI.”

Uh…what? The fact that ‘your’ responses are not shown allows you to imagine them. Instead of putting words in the protagonist’s mouth that would ring false–“I would never say that”–the player is able to imagine whatever declarations of love are most compelling for them. This ENHANCES the attachment the player feels to the characters.

You’ve reached a weird conclusion. Interesting.

Emily Short’s take on this game:

http://www.gamesetwatch.com/2010/05/column_homer_in_silicon_the_mi.php

http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/28629/Analysis_Examining_Digital_A_Love_Story.php

John — That wasn’t my experience… I am intrigued by your idea about empathy emerging simply because there is a place for it to go. Hmmm. I really enjoyed the game, but I didn’t feel emotionally engaged for even a second.

Cuc — All of my conclusions are weird. What’s the point of a predictable opinion? 🙂

“thereby reinforcing the nostalgic vision of an uncivilised internet frontier in which even the lowliest of nerds could battle the odds and win the heart of a beautiful computer”

Um, I think the nerds were trying to *avoid* hooking up with the bots and 14-year old boys and the dogs on the internet.

Also, I think if Digital Works, it’s because the AI character is not emotionally hollow but holds emotional resonance. You may be distanced from the ‘protagonist’, but not Emilia; you don’t feel teh angsty teen lurves but you certainly feel *her*. You caring about the AI is kind of the point of the ending where you can protest its decision to self-terminate. The same goes for Fallout; the cultural idiosyncracies and ambiance of Raygun Gothic US are satirized and tongue-in-cheek, but the characters that find themselves within the Fallout world are real and relatable, not cardboard cutouts. You laugh at ‘the game’ not the players, so to speak. If you don’t care whether or not a town full of people you’ve been living with gets nuked or not, then Fallout (3) hasn’t done its job.

Perhaps, in your experience, BSSes did only function as ‘dead letter drops for text files and pirated software’, but my experience in the early ’90s was far different. The BBSes in my hometown had incredibly active message boards, obnoxious games like pimp wars, and one large board even had a six line setup with a chat-room program. I got into the whole ‘scene’ in my early adolescence, and met a lot of the people who went on to become my closest ‘real life’ friends on local bulletin boards that I discovered in essentially the same way as the procedure presented in the game.

So I think it’s interesting that you’ve classified the game as something of failure based at least in part on that perception — if i’m correct, you’re arguing that the story doesn’t ring true because it displays a level of personal involvement never actually shown on real bulletin boards, thus breaking the fiction, while I’d argue that you’re basing your view of “BBS Culture” on a selective sampling and missing the emotional resonance of the game as a result.

I enjoyed your more generalized statements about nostalgia, but I do think some of your criticisms of Digital are a little off-base. In my case, I haven’t played a game that gave me a ‘sad feeling’ like that one did in quite a while.