I am very pleased to publish my talk from Improving Reality 2013. Here is the video version… followed by my slides and script, because, well, I’m a writer, and not a natural orator. (I need to work on that, I think.)

IR was a day of fascinating talks, and I heartily recommend all of them; they can be found on the Lighthouse Arts YouTube channel. Particular favourites include Keller Easterling (who was the very definition of “hard act to follow”), Justin Pickard (favoured guest of this parish in years past, and getting sharper and more dangerous by the month) and Georgina Voss (who’ll make you think about choose-your-own adventure books and venture capitalism in a totally new way).

So, on with the show…

#

[Slides and script below the cut…]

#

**greetings, ad-lib’d**

In Douglas Adams’s Life, the Universe and Everything, Arthur Dent and Ford Prefect are watching a test match at Lords when a spaceship (built, as I recall, to resemble a small Italian bistro inexplicably turned on its side) lands on the ground in the midst of an over. Not a person notices it but Ford and Arthur, those seasoned and cynical galactic hitchhikers.

That’s because the spaceship is protected by something called a Someone Else’s Problem Field, whose inventor realised that while making something invisible is incredibly difficult, making something appear to be someone else’s problem is very, very easy.

Think of it as the flipside of the dubious “nudge psychology” that Mister Cameron’s policy machine is powered by, if you like.

The Someone Else’s Problem Field around infrastructure is, ironically enough, a measure of its ubiquity and success. You don’t think about it because you don’t need to; it just works, and when it doesn’t, there’s a phone number you can not bother calling, because they’ll only put you on hold anyway, and by the time you get through it’ll probably have fixed itself, so why bother? You pay for these things to work, and – most of the time – they do. You pay for them to be Someone Else’s Problem.

Being reminded of infrastructure is rarely pleasant. It’s no fun to turn your tap and have nothing come out. It’s a different sort of not-fun when you discover that a wind-farm, town bypass or high-speed train line is scheduled to materialise near your house, or when protestors camp out on your driveway to fight a fracking company. Infrastructure is meant to make life easier, not harder. The better it gets at the former, the more painful are the moments when it does the latter.

The golden age of British infrastructure was surely the Victorian era, thanks to a combination of ambition, new technological developments, and an exploitable underclass workforce. In those days, infrastructure primarily benefitted the middle and upper classes; if you were working class, you were likely one of infrastructure’s many unsung human components, and new infrastructure was far more likely to spoil your immediate environment than improve it. To the middle classes, though, infrastructure – especially the railways – was progress incarnate, a living force in the world. Victorian painting and literature is full of infrastructure, sometimes as hero, sometimes as villain, depending on the target audience: majestic bridges in oil on canvas for the gallery-goer, train-wreck penny dreadfuls for the proles.

It was all new, and people wondered what it meant.

Speaking earlier this year at Next13, Anab Jain of Superflux, who were kind enough to publish my original essay on infrastructure fiction, described design fiction as follows:

“These projects bypass the established narratives about the present and future that create the hypnosis of normality, and in doing so allow for an emotional connection with the raw weirdness of our times, opening up an array of possibilities.”

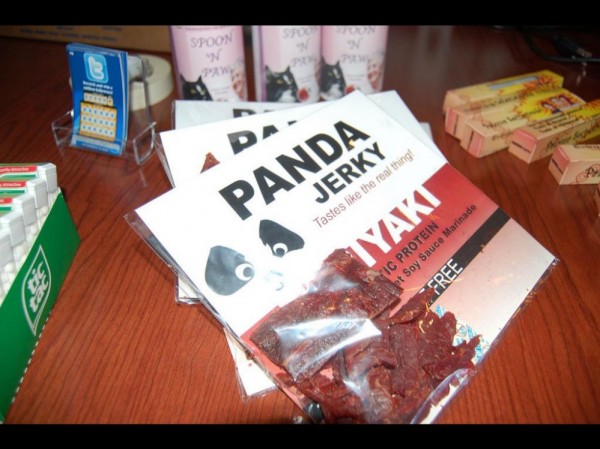

It’s the best and most concise description I’ve found of what design fiction does. How design fiction does what it does, on the other hand, is a much more open question. Its techniques emerge from the mediums it makes use of – so perhaps we might wink at McLuhan’s ghost, and say that the medium is the method. Design fiction can be written, it can be still images or mock-up packshots, a fake promo spot or mock documentary video, or even performance theatre or live-action roleplaying. I don’t know if there are any design fiction games, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there were.

The main requirement, it seems to me, is that in order to be effective, design fictions must believe in themselves – though there’s some tricky caveats here that I’ll return to later on. But for now the point is that simply putting together a project proposal for some wacky new idea isn’t enough. If you present a design fiction as a proposal, you give the audience permission to say “but that’ll never make it to market!”, which ends the conversation instantly. (You might as well try feeding social metaphors to hard science fiction fans.)

So you don’t propose a solution to the problem. No; in a design fiction, you imagine the problem to already be solved – and then you ask what that solution has to say about the problem that you hadn’t considered beforehand, and what it tells you about the future in which it actually gets built.

Asking what an object or structure means is an intrinsic part of what designers, architects and artists do all the time. It’s not natural for engineers, though. Engineers are practical people; they build things to spec, they keep the lights on and the trains running. To be clear, this isn’t to claim that engineers have no imagination – far from it. Engineers have plenty of imagination, but it is directed very differently. Engineers solve problems; they imagine “how”. The artist, by contrast, imagines “why”; the engineer’s problem is the end product of the artistic process.

Before we can ask what infrastructure means, however, we need to first determine what infrastructure is; we need to define it, sketch out the field of enquiry.

The Institute of Civil Engineers defines infrastructure as “the physical assets underpinning [the UK’s] networks for transport, energy generation and distribution, electronic communications, solid waste management, water distribution and wastewater treatment”.

Exciting stuff, right? But this purely materialistic conception of infrastucture, so useful for an engineer, gets the rest of us everywhere and nowhere at once, because it hides the social impact of infrastructure behind functional generalities. To reveal that social impact, we have to destroy two assumptions.

The designer usually takes infrastructure as a given, if they think of it at all; it’s just a set of standards and protocols upon which they can rely to support certain functionalities in their designs. Infrastructure is the oxygen of the design profession, if you like; always invisibly ready to breathe life and capabilities into their creations.

Assumption A isn’t so much wrong as it is incomplete; it assumes a simplex Y-follows-X causality, “if infrastructure, then technology”, but the reality is more complex. Of course infrastructure enables technology… but technology has at the same time been a major driving force in the development, expansion, enhancement and ubiquity of infrastructure. Infrastructure and technology have always been locked in a symbiotic coevolution, to the extent that the division implied by the separate terms is largely illusory; infrastructure and technology are two sides of the same coin, if you like, but infrastructure is the ugly, boring and pragmatic side, while technology is flashy, exciting and transformative.

Consider Edison, arguably most famous for the invention of the incandescent lightbulb; we tend to forget that Edison and the other electrical inventors of the time were struggling to crack the lightbulb problem in order that they had a product which might convince people that they should get connected to the early electrical supply services. The lightbulb concretised the potential of electricty to do useful work in the home, turning a what had up to then been an abstract and rather frightening scientific discovery into a household utility – and the rest is, quite literally, history.

Assumption B is, as far as I can tell, a sort of late-stage mutation of Marx’s commodity fetish, in that it manifests as the erroneous notion that the value and utility of a technological object is located entirely within the object itself.

Take this power-drill, here; fairly standard tool of the modern household. If I was to ask you what the power-drill can do, you might say that it can drill holes in your walls, right? Well, no – it is the drill-bit that drills the holes. The motor unit of the power drill simply enables you to use the drill-bit to make more holes more quickly before getting tired, and in a greater variety of materials than you could make using elbow grease alone. The drill-bit is the tool; the power-drill is a function-specific extension of the infrastructure, an interface between the drill-bit and the abstract world of harnessed energy.

When you connect a device to an infrastructure, the latter is effectively subsumed by the former. To use a literary term, it’s a sort of metonymy: the power and potential that we imply when we speak of a power drill is actually the power and potential of the electricity grid, an electrical spirit that animates the drill’s unliving body. The power-drill is neither tool nor infrastructure; it is, quite literally, something in between.

If you don’t believe me, go unplug that power drill from the wall, take it somewhere there are no wall sockets, or even just the wrong sort of sockets. Or take a power-shower to some place without a water distribution mains, or your smartphone to somewhere where there’s no signal coverage.

Ain’t much use to you now, is it?

This constructive disillusionment is what infrastructure fiction should aim to achieve; it must problematise not just a discrete technology or service, but the entire infrastructural stack on which the technology or service is dependent. Infrastructure fiction must collapse the Someone Else’s Problem Field, finger-snap you out of the hypnosis of normality. It must reveal the hidden metasystem that underpins everything you do.

It’s all well and good to shatter illusions, but infrastructure fiction should also present alternatives, substitute visions. Bruce Sterling talks a lot about bad forms of design fiction, and makes the point that design fiction shouldn’t be hoaxy, deceitful or packed with F.U.D. – fear, uncertainty and doubt. As I said earlier, a design fiction must believe in itself to do its work – but it must simultaneously signal its fictionality, however subtly.

This is, not at all incidentally, the central challenge to writing good science fiction, and the reason why airport technothrillers can feel less believable than out-and-out science fiction; the latter is almost always winking at the audience, while the former tries to pass for realism, and thus falls into fiction’s equivalent of the uncanny valley.

This isn’t just a matter of literary aesthetics, though. Sterling is seeking an ethical dimension to design fiction, because he knows at first hand the power of the techniques he’s discussing, and he’s cynical enough to know that powerful techniques work just as well in bad hands as good ones. The term “diegetic prototype” was coined by David Kirby in a paper called “The Future Is Now: Diegetic Prototypes and the Role of Popular Films in Generating Real-world Technological Development.” Kirby’s paper is a discussion of the way that technologists and designers are drafted into sci-fi film production teams so as to get the tech in the movie’s storyworld looking convincing. But we’ve now reached a point where films are becoming a vehicle through which these designers can inject their design ideas into the cultural soup, acting as what Kirby calls “pre-product placements” – a particularly apposite term, given the touchscreen interfaces of Minority Report are a prime example.

My colleague Scott Smith talks a lot about “flatpack futures” – especially those grotesquely aseptic lifestyle technology ads that are suddenly everywhere, showing clearly how the purchase of a certain branded piece of hardware will situate you in a blandly contemporary and impossibly unsmudged ideal of the middle-class Western lifestyle. There’s a crude sort of diegetic prototyping at work here, too. The difference between this stuff and “proper” design fiction is that flatpack futures exchange the critique of technology for the uncritical advocacy of technology. The problem is that to Josephine Public, the difference between foresight and marketing may not be apparent, especially in a medium that relies on the internal coherence of false realities to do its work.

Indeed, one might make the argument that transhumanism is a great example of a very sophisticated and collaborative shared-world design fiction veneer over a cynical me-first libertarian ideology, which in turn obscures an elaborate Ponzi scheme based on cryogenic life insurance policies and unfalsifiable proposals for AI research grants… but as I don’t have a lawyer on retainer, I’d not want to suggest such a thing in public.

However, there’s a value even to flatpack futures, in that the biggest ones get a lot of public attention, and hence a lot of public critique. It was very generous of Elon Musk to come out with a perfect example of a flatpack-future infrastructure fiction so shortly after I coined the term – thanks Elon, if you’re watching; the cheque’s in the mail, yeah?

But really, it’s a great example of design fiction done badly: for instance, the locations the proposal joins together make it very obvious that Musk’s ideal customer is himself – in stark contrast to the PayPal user interface, whose ideal customer is presumably a human being of infinite pateince. But screw demography and market research, this isn’t some pinko cryptosocialist proposal for improving the general human condition; this is serious Silicon Valley technoshit, blithely presented as a shovel-ready project just waiting for the right about of venture capital to light the blue touchpaper – so stand well back, ladies and gentlemen!

It’s also wrong in many, many ways; there weren’t quite so many robust critiques of Hyperloop as there were breathless fawning reblogs of the pretty pictures, but there were quite a few, taking the idea to task from every angle: geography, economics, materials, engineering, health and safety, so on and so forth.

I hope it’s clear now, if it wasn’t before, that infrastructure fiction is less a methodology than a manifesto, a plea for a paradigm shift in how we think about our increasingly technology-saturated world. How exactly you take it on board, what exactly you do with it, will depend on who you are and what it is you do.

When I talk to my engineer colleagues about infrastructure fiction, I tend to pitch it as another sort of modelling, albeit almost purely qualitative and conceptual by comparison to the models they use most often. The tricky bit to get across to them is that in a design fiction, failure is not only instructive but desirable; engineers rarely waste time thinking about something which they already know can’t be built. This is the good thing about Musk’s Hyperloop: it got thousands of people thinking imaginitively and critically about infrastructure, talking about what it means, about what it should do, and how and for whom it should do it.

Try having that conversation around HS2, by contrast, and all anyone cares about is how much it’s going to cost, and whose back garden it’s going to run through. HS2 is too real and political a problem, too rooted in the here and now, for us to get to grips with the deeper questions. By contrast, the imaginative and speculative bits of Hyperloop serve to dispel Anab’s hypnosis of normality and open up the possibilities and pitfalls for discussion – and if that’s all it achieves, I still think it’s done good work. (I rather doubt Mister Musk would agree with me on that, but there you go.)

For artists, writers, designers and theorists and thinkers, however, infrastructure fiction is best described as a call for you to radically change the way you understand the role of technology in your lives, to look afresh at the relationships between the things you do and the systems that make it possible to do them.

I’m not asking you to “think outside the box”, here. On the contrary, I want you to think exactly about the box. Infrastructure fiction isn’t about transcending constraints, it is about coming to terms with our constraints as a civilisation, about understanding their nature, and internalising the systemic limits that come from living in a sealed ecosystem with finite resources.

Nor do I want you to, as one response to my essay suggested, “write more stories about bridges” – though if you’ve got a story to tell about bridges, I think you should go ahead and tell it. The clue’s in the name: infrastructure fiction is obviously interested in infrastructure, but it’s fiction, and fiction is for and about people. So by all means, write a story about a bridge, but make the bridge more than a prop, more than a setting or a symbol; make it a character in its own right, an agent in the network of society of which it is a structural and functional component.

But write about people, too, because they’re most reliably invisible part of any infrastructural system: not just the people who use it, but the people who maintain and operate it, the people who protest against it, the people who blow it up or steal bits of it, even the people who live among its ruins. Write about the relationship that people have with the bridge, and that the bridge has with the people. Remember that neither makes sense in the absence of the other.

Think about the box. Think about constraints.

Failure is instructive. Thank you.

ENDS

Mind blown: “Asking what an object or structure means is an intrinsic part of what designers, architects and artists do all the time. It’s not natural for engineers, though. Engineers are practical people; they build things to spec, they keep the lights on and the trains running. To be clear, this isn’t to claim that engineers have no imagination – far from it. Engineers have plenty of imagination, but it is directed very differently. Engineers solve problems; they imagine “how”. The artist, by contrast, imagines “why”; the engineer’s problem is the end product of the artistic process.”