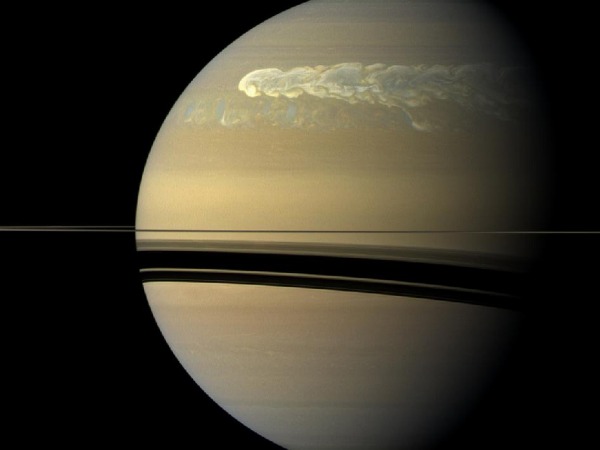

T’ain’t just us Earthlings experiencing erratic weather, y’know; check out this rather vast storm on Saturn, courtesy the Cassini probe. Audio is also available.

Tomorrow, if all goes to plan, the Space Shuttle will launch for its very last mission before retirement (to fates as yet undecided – museum piece or rich man’s megabauble?) Cue inevitable soul-searching all over the place; here’s The Economist sounding the death knell for outer space.

Tomorrow, if all goes to plan, the Space Shuttle will launch for its very last mission before retirement (to fates as yet undecided – museum piece or rich man’s megabauble?) Cue inevitable soul-searching all over the place; here’s The Economist sounding the death knell for outer space.

It is quite conceivable that 36,000km will prove the limit of human ambition. It is equally conceivable that the fantasy-made-reality of human space flight will return to fantasy. It is likely that the Space Age is over.

Today’s space cadets will, no doubt, oppose that claim vigorously. They will, in particular, point to the private ventures of people like Elon Musk in America and Sir Richard Branson in Britain, who hope to make human space flight commercially viable. Indeed, the enterprise of such people might do just that. But the market seems small and vulnerable. One part, space tourism, is a luxury service that is, in any case, unlikely to go beyond low-Earth orbit at best (the cost of getting even as far as the moon would reduce the number of potential clients to a handful). The other source of revenue is ferrying astronauts to the benighted International Space Station (ISS), surely the biggest waste of money, at $100 billion and counting, that has ever been built in the name of science.

Well, space cadet is as space cadet does, right? Here’s a response from Paul Gilster at Centauri Dreams:

As commercial space efforts move forward, a broader defense of a human future in space has to take the long-term view. Given the dangers that beset our planet, from ecological issues to economic turmoil and the potential for war, can we frame a solution that offers a rational backup plan for humanity? Planetary self-defense also involves the need for the tools to alter the trajectory of any object with the potential to strike the Earth with deadly force, and that means expanding, not contracting, our space-borne assets. Such work is not purely technical. It also teaches the invaluable lesson of multi-generational responsibility and holds out the promise of frontiers. Such challenges have enriched our early history and provide us a clear path off our planet.

We’re also a curious species, and it’s hard to see us pulling back from the challenge of answering the crucial question of whether we are alone in the galaxy. There is a huge gap, asThe Economist points out, between where we stand with space technology today and where we fantasized being as we looked forward from the Apollo days. But a case can be made for steady and incremental research that gives us new propulsion options and broadens our knowledge of how life emerges even as it protects our future. A future that includes gradual expansion into space-based habitats and the exploitation of our system’s abundant resources is an alternative to The Economist’s vision, and it’s one the public needs to hear. The infrastructure that it would build will demand the tools and the skills to move ever deeper into our system and beyond.

An editorial piece at New Scientist is similarly – if cautiously – optimistic about a NASA renaissance rather than a recession; there’s certainly lots of can-do rhetoric from them, not to mention hungry competition from up-and-coming nations with cash to spend and ambitions to fulfil. But given that the new proposed NASA budget will axe projects like the James Webb orbital telescope – Hubble’s successor, basically – I’m not sure how much mileage there is in brave words and stoic chest-thumping. Hell, some folk are even wondering whether the Space Shuttle program itself wasn’t a massive and very costly mistake [beware irritating interstitial ad; via Chairman Bruce]:

The selection in 1972 of an ambitious and technologically challenging shuttle design resulted in the most complex machine ever built. Rather than lowering the costs of access to space and making it routine, the space shuttle turned out to be an experimental vehicle with multiple inherent risks, requiring extreme care and high costs to operate safely. Other, simpler designs were considered in 1971 in the run-up to President Nixon’s final decision; in retrospect, taking a more evolutionary approach by developing one of them instead would probably have been a better choice.

[…]

Today we are in danger of repeating that mistake, given Congressional and industry pressure to move rapidly to the development of a heavy lift launch vehicle without a clear sense of how that vehicle will be used. Important factors in the decision to move forward with the shuttle were the desire to preserve Apollo-era NASA and contractor jobs, and the political impact of program approval on the 1972 presidential election. Similar pressures are influential today. If we learn anything from the space shuttle experience, it should be that making choices with multidecade consequences on such short-term considerations is poor public policy.

And if we’ve learned anything from life in general, it’s that expecting politicians to think further ahead than the next election is a doomed enterprise. For my money, I think space exploration still has a future, but – in the West at least, and particularly the US – that future will be increasingly dominated by private enterprise.

This is a nicely resonant topic for me, as it happens. I spent last weekend in London for the Science Fiction Foundation‘s Masterclass, and one of the topics we tackled was the representation of space exploration in contemporary science fiction texts. The inescapable conclusion (for me, at least) is that space sf is dominated by a sense of nostalgia, but also – especially in what you might refer to as “heartland” sf venues like Analog and Asimov’s, whose readership were around to be inspired by the hollow rhetoric of the Apollo program – there’s a void at its heart.

Old-school space advocates have a tendency to talk about space in terms of glory, accomplishment and a sort of noble and patriotic heroism, a taming of the wild rolling plains… indeed, that whole “final frontier” riff probably sounds even sweeter, after ten misguided years of failed attempts to plant the stars’n’bars on other more mundane frontiers – as far as we know, space has no uppity natives to object to your delivery of democracy and neoliberal corporatist economics, which gives it a blank-slate patina that you can’t get anywhere else.

But therein lies the problem, and – or so I suspect – the reason why the American Dream (Extraterrestrial Edition) has faltered: beyond that noble rhetoric, the Apollo program was an ambitious (and successful) pissing contest with Russia. All the other motivations and ideals were grafted on after the fact, and they’ve all fallen away like burned-out heat-shielding. America still wants to be doing stuff in space, but it doesn’t really know why; the narrative has collapsed, and that’s why there’s no money for it.

Meanwhile, out in the BRIC, growing economies are looking for trophies, boasting rights and… well, new frontiers. The torch wasn’t passed; it’s been snatched by the trailing pack, and it’ll be interesting to see what they do with it. I suspect it’ll turn out that pioneer bravery and Competent Persons will have their own renaissance, and turn out not to be something exclusively American in character after all… but ambition always comes at a price.

There’ll be more stories to tell about space, I feel sure. But I’ll bet my boots that an increasing proportion of ’em won’t be written in English. 🙂