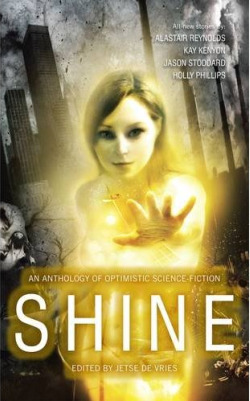

Shine: An Anthology of Optimistic Science-Fiction by Jetse de Vries (ed.)

Shine: An Anthology of Optimistic Science-Fiction by Jetse de Vries (ed.)

Solaris Books, April 2010; 416pp; £7.99 RRP – ISBN13: 978-1906735661

I’ve been talking about Jetse de Vries’ Shine project for a long time now, for a number of reasons: not only is Jetse a good friend and former colleague, but I’m a sucker for manifestos and movements that attempt to turn against the grain within their chosen field. I supported the call for optimistic science fiction for the same reason I supported the Mundane SF movement, in other words, and in the same manner – not in hope of seeing one hegemony replace another, but in hope of seeing the landscape change a little.

Only time will tell whether Shine will cause more than a momentary blip on the stylistic timeline of science fiction, of course. But a number of the stories contained within it seem to prove Jetse’s thesis, namely that you don’t have to write a dystopian or post-apocalyptic future to create an engaging science fiction story. Stated like that, it sounds like something of a tautology… but Jetse’s struggle to get a decent crop of submissions before the cut-off date suggests that there’s some sort of block over the idea. Whether that’s something to do with the prevailing culture of sf, or something to do with the tastes of individual short story authors, is a question that remains to be answered over the long term. Or never answered at all, perhaps.

For this reader at least, the anthology’s only reprint story is one of the most successful exponents of the theme: Holly Phillips’ “Summer Ice” is a beautifully written and genuinely moving slice of a very mundane near-future life, and it well deserves the praise it has received before… though much like Jetse I was astonished to discover many readers consider it to be a fantasy (which in itself says something important about how the venues in which a story appears may affect the categories it is perceived to belong in – how many extant stories might become ‘optimistic near-future sf’ if collected in a book of such?).

Die-hard sf readers might find the Phillips more than a shade too mundane, however. The ‘harder’ science fiction pieces might be more to their taste, such as Jason Stoddard’s “Overhead”, whose optimism lies in deciding that a moon base is still an achievable human goal, even if it’s not built as a nation-state’s economic beachhead, diplomacy bauble or macho chest-thump. Eric Gregory likewise goes for technical plausibility in “The Earth of Yunhe”, though he keeps things closer to home as his characters use social networks mobilise support for rebuilding a climate-wrecked city with nanobots in the soil.

Madeline Ashby’s “Ishin” is also very much a story-of-nearly-now, and probably my favourite of the lot; compassion and confusion among two military-embedded tech-geeks in some unspecified desert theatre of war, delivered with incredible narrative control and voice. Stepping a little further out in time, Mari Ness’ “Twittering The Stars” echoes Stoddard’s dreams of humans beyond the gravity well, though her spacepersons are on a scientific mission; the reversed Tweet-stream format is a Zeitgeisty update on the epistolary or diary-style story that will look dated long before its underlying theme of the fragility of human life in space does. Last but not least among what we might label the ‘hard optimist’ stories are two short and almost literary pieces: Paul Stiles’ “Sustainable Development” is a homily about foreign aid, technology and gender in Africa, and “Scheherezade Cast In Starlight” by Jason Andrew draws hope – and emotional clout – from the role of social media in the recent democratic protests in Iran.

Shine also boasts a number of stories whose depictions of the future are more wry or metaphorical. Lavie Tidhar’s “The Solnet Ascendancy” flips conventional notions of foreign-funded aid work in developing nations on their head, and sees a remote Pacific archipelago bootstrap itself to somewhere approaching low Earth orbit once it gets its hands on the tools that the rest of the wired world already takes for granted. Meanwhile Gord Sellar uses the argot and philosophy of the pick-up artist movement to sneakily suggest that politics and activism aren’t perhaps as different as the two camps tend to think in “Sarging Rasmussen: A Report (by Organic)”. Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s “Seeds” is another truism turned on its head, as a GM crops troubleshooter finds that his clients aren’t quite as trapped as they’re meant to be, and Kay Kenyon turns an idea for cleaning up the maelstroms of junk in our oceans into a (literally) moving symbol of the triumph of the heart, albeit achieved by shedding some of the plausibility towards the end of the tale.

A few of the stories were less than successful for me. For example, “Paul Kishosha’s Children” by Ken Edgett, while uplifting and visionary in its underlying themes of genuine progress and aspirational education in Africa, suffers through a conspicuous lack of a tangible antagonist – though it’s worth mentioning that I’ve had similar problems with one of Jetse’s own stories (coincidentally also set in Africa), so this is perhaps more a matter of taste than technique, or maybe a failing on my part as the reader to give Africa’s problems the narrative weight that they would have for someone who has seen them first hand. Meanwhile, Jacques Barcia’s “The Greenman Watches the Black Bar Go Up, Up, Up” is disappointingly hampered by its stylistic overload – there’s a fine story in there, perhaps even two of them, but too much stuff is crammed into too small a space for the tale to breathe freely.

I’m less hesitant about disliking Eva Maria Chapman’s “Russian Roulette 2020”, however; it reads to me like exactly the sort of huggy-feely sockpuppetry that vocal opponents of the anthology’s premise suggested would be its inevitable result, like Skinner’s Walden Two updated to suggest that if Western kids would just turn off teh damnz intarwubs for ten minutes, eat granola and embrace a more rustic way of life (except in such situations as teh intarwubs iz useful, natch), then everything would be just great. That thesis has some merit, perhaps, but Chapman’s fictional chops aren’t up to making her characters and situations sufficiently plausible to carry her argument… or to make the story an interesting read, for that matter. According to Jetse’s introduction, Chapman had never written sf before submitting to Shine; it shows.

The real odd-one-out is arguably also the book’s biggest name, at least to the UK market. Alistair Reynolds’ “At Budokan” is brilliant fun and brings a whole new subtext to the music critic’s epithet of “rock dinosaur” – the sort of story I’d rather like to publish more of here at Futurismic, in fact. But of all of the stories in Shine, its connection to the theme of optimism is the most tenuous. As gonzo comic relief, though, it’s well positioned… and should probably crop up in a few year’s best lists, if there’s any justice.

I’ve often heard a truism that states “if you like more than half of the stories in an anthology, then it’s a success”, and by that metric Shine is surely a good book. And as far as supporting Jetse’s thesis (and the ongoing Optimistic SF project, if there is to be such a thing) is concerned, it also ably demonstrates the potential of optimistic science fiction to entertain and speculate at the same time.

But most of all, it highlights the incredible energy and enthusiasm of its editor, and his willingness to stick to his guns in the face of derision and disinterest. That energy didn’t just get spent on reading, selecting and and editing submitted stories, but also flowed out into discussion, advocacy, and a whole shed-load of hard work, editorial and promotional alike. For all of these reasons, I sincerely hope there’s a second anthology in the Shine series, and maybe more after that.

How’s that for optimism?

“…there’s some sort of block over the idea [of avoiding distopian themes]. Whether that’s something to do with the prevailing culture of sf, or something to do with the tastes of individual short story authors…”. Maybe, the point is simply that sf is concerned with long-term tendencies, and the current state of the world does not encourage optimism (in writers and non-writers as well).

I bought this book but was so frustrated with it that I even tried reading the stories from the back. First, the stories are hardly stories. There are no “plots”, mostly “descriptions” type of prose of scenarios. Second, many of the items in the collection are hardly coherent. I know I am “politically incorrect” not to lavish praise and swoon over it but it is deceiving to science fiction fans if I am not truthful. I threw it away after trying to read a few of its so-called stories.