- Lithium

I’m old enough to remember when video games were comparatively simple things. For example, I remember the side-scrolling video game adaptation of Robocop (1988). Relatively short, Robocop had you shooting and jumping your way from one side of the world to another. Once you got to the end of one world, you moved to another, and then another… and then the worlds started repeating themselves in slightly different colours. These games were simple to understand: you immediately knew what you were expected to do and what constituted victory. Nearly twenty-five years on, video game technology has advanced to the point where games are beginning to acquire the complex ambiguity of the real world — and with this complexity comes difficulty.

Simple games are satisfying because they tell simple stories. Complex games, on the other hand, can often be profoundly unsatisfying, as they also attempt to tell simple stories. An excellent example of the failure to develop complex narrative techniques to fit complex games is the narrative wasteland that is Bethesda Studios’ The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011). Far more than a poorly written game, Skyrim is a damning indictment of video game story telling, in so far as it completely fails to imbue the events of the world with any kind of emotional significance. Skyrim is a deep and complex game, yet the experience of playing it is very much akin to spending a week on lithium.

But then, maybe the game is just being honest with us?

- Emotional Reductionism

To understand the world is, on some level, to explain it — and to explain the world is to talk about what is happening on one level in terms of a second, more basic level. Thus we talk about human behaviour in terms of biology, of biology in terms of chemistry, of chemistry in terms of physics and physics in terms of mathematics. Sooner or later, everything boils down to mathematics.

This reductionist creed stands at the heart of the scientific method and the Enlightenment project as a whole. The challenge of reductionism lies in taking all aspects of a particular level of explanation and accounting for them in terms of a more basic level. Thus, a successful account of human behaviour would take every aspect of our daily lives and explain them in purely biological terms. This is why prediction is so important to the scientific method: if one cannot predict what will happen on one level based upon our understanding of the more basic level, then one has not accounted for everything on that first level, and the reduction has failed.

One can look upon the history of human culture as a series of attempts at accounting for human psychology in more basic terms. Indeed, when writers tell stories and create characters they do so with a basic understanding of the causes and effects underpinning human behaviour. Bad characterisation is what results when the author’s psychological model fails to map onto ours. Many introductory courses in the humanities account for human culture in terms of our capacity to generate more and more sophisticated models of human psychology. Thus Homer’s Greeks are less ‘realistic’ than Dante’s saints, and Dante’s saints are less ‘realistic’ than Flaubert’s disaffected middle-class women.

One of the most interesting ways of looking at contemporary culture is to assess which kinds of models creators used to inform their writing. Consider, for example, the Freudian assumptions that go into TV series such as The Sopranos and Six Feet Under, or the existential vision of human nature that informs the writings of Sartre and Camus. While most creators are swift to claim that their approach embodies greater ‘realism’ than that of their contemporaries, it is clear that all of these works are simply a reproduction of reality rendered in terms of a pre-existing theoretical understanding of human nature. Depending upon which theoretical understanding of humanity they tend to hold, creators focus on different aspects of the human experience, which is why you seldom get existential romantic comedies but frequently get Freudian takes on family relations.

Being a video game, Skyrim’s vision of human nature must ultimately reduce down to a series of binary instructions to circuitry. However, while this is true of all video games, Skyrim’s vision of human nature comes across as particularly mechanistic and reductionist. Indeed, despite being modelled on the epic fantasy stories of the Tolkienian tradition, Skyrim presents the life of its characters as nothing more than a series of interlocking to-do lists: Go here, go there, kill him, kill her, save the world, collect butterflies. Aside from reducing the complexities of life to a series of to-do lists, the game also refuses to impose any kind of hierarchy on the relative importance of difference missions; as a result, saving the world appears no more or less important than ruining the local bard’s love life.

On one level, this psychological relativism is a serious flaw in the game, as it sets up what Clint Hocking calls a case of ludonarrative dissonance — in that the game is supposedly about the urgent need to save the world, but saving the world is really just another way of making ends meet. Like so many RPGs, Skyrim is nothing more than an extended pursuit of easily quantifiable improvements. On another level, this psychological relativism results in a game world that is utterly drained of meaning and emotion:

Q: Why did I complete that mission?

A: Because it allowed me to level up.

Q: Why did I put my character in danger?

A: Because I thought that that heavily guarded fortress might contain some decent loot.

Q: Why do I care if I level up or get my hands of decent loot?

A: Because it makes my character more powerful.

Q: Why do I want my character to become more powerful?

A: Because I want to take on tougher missions and so level up and gain more loot.

While all video games ultimately reduce down to mechanical feedback loops and branching decision trees, most game designers soften the impact of their mechanical reductionism by hiding it behind a series of dramatic conceits that place the events of the game within a particular context which, though meaningless in mechanical terms, will provide the players with a context through which to understand their in-game actions, a context that will allow them to connect on an emotional level with the plots and characters of the game.

- Applying Meaning to Mechanics

Consider the classic arcade game Breakout (1976). Based on Pong (1972), Breakout featured a paddle that moved horizontally back and forth across the bottom of the screen in order to intercept a ‘ball’ that would rebound back up the screen and destroy one of a series of blocks. The aim of the game was to keep batting the ball back towards the blocks until they were all destroyed and you moved on to the next level. Looking back at Breakout, one of the most extraordinary things about it is the absolute failure to situate the game in any kind of narrative context. Breakout is not about escaping or about saving someone or about exploring the intricacies of the human condition. It is a game about destroying blocks.

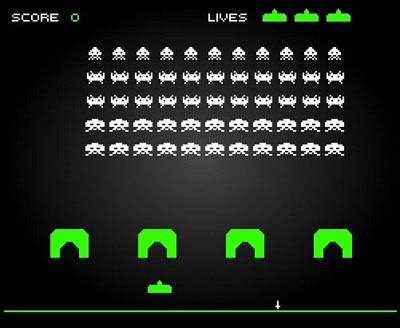

Space Invaders (1978) differs from Breakout in so far as its title is an attempt to provide a context for the events of the game. On a purely visual and mechanical level, Space Invaders is not that different to Breakout, but because its title forms a link to the films and literature of science fiction, the game suddenly acquires a narrative context. It tells a story and invites us to invest our emotions in the pixels that comprise the game.

This attempt to forge an emotional connection between the player and the game reached maturity in the 1980s when games such as Super Mario Bros (1985) included primitive cut-scenes that situated the events of the game within a broad romantic quest narrative in which a pair of plumbers battled evil minions in order to save a beautiful princess.

As time has passed, game designers have become more and more proficient at placing their games within particular cultural and narrative contexts. These contexts not only allow players a good deal of freedom and agency, they also provide them with a basis for imbuing in-game actions with a certain degree of emotional significance. This process of imparting meaning to in-game events draws on two different but ultimately overlapping classes of technique:

The first class of technique is the one pioneered by Space Invaders, namely that of forging a connection between the events that take place within the game and a wider set of cultural narratives. Humans seldom accept things purely at face value; instead they approach every new situation with a set of expectations drawn on previous experience. When people began feeding money into Space Invaders, they experienced the game not just in terms of that game’s content but also in terms of a literary and cinematic tradition that stretched back at least as far as the 19th Century. When people reacted to the in-game events that made up Space Invaders, they were not merely reacting to Space Invaders but also to films such as Star Wars (1977), Forbidden Planet (1956) and the novels of Robert A. Heinlein and H.G. Wells. By naming their game Space Invaders, Taito and Midway were not just inspiring themselves from popular culture, they were also tapping into a set of conditioned responses resulting from decades of reading and watching: conditioned responses that invited people to connect on an emotional level to what they were seeing on screen.

This technique is still visible today in the tendency of games to borrow characters, settings and plotlines from other cultural artefacts. For example, when we react to the events depicted in L.A. Noire (2011) and Red Dead Redemption (2010), we are not just reacting to the events depicted in the game but also to the events depicted in the novels of James Ellroy and the films of Sergio Leone. When seen in this light, the derivative nature of game characters and plots are not so much a failure of the imagination as they are a deliberate attempt to tap into a set of emotional responses to the work of other writers and directors.

This technique is also evident in the tendency to draw on real world and historical fears to provide a narrative framework for such military shooters as those of the Battlefield and Call of Duty franchises. The reason why both Battlefield: Bad Company 2 (2010) and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (2009) present us with plots revolving around Russian invasions and WMDs is that these were sources of popular anxiety for American audiences; when people engage emotionally with those games they are engaging not just with their content but also with the legions of newspaper articles, blog posts, rolling news reports, novels and non-fiction books that have been written about WMDs and an increasingly belligerent and autocratic Russian state.

The second class of technique is far more conventional, in that it involves using traditional literary devices such as character, plot and dialogue to invest the events of the game with an emotional charge. While elements of this technique are evident in the decision to populate games with recognisable characters such as Mario or Sonic, the technique only really reached maturity when games acquired the capacity to mimic the cinematic narrative form and its visualised depiction of characters engaging with each other in a fictional world. The fact that game designers and writers are still struggling with this approach to narrative is evident in the fact that there are far more memorable video game characters than there are memorable video game stories. Indeed, for every death of Aerith in Final Fantasy VII (1997) there are dozens of Revolver Ocelots, GLaDOSs, Gordon Freemans and Lara Crofts. In fact, now that I come to mention it, the death of Aerith is only a ten-minute segment of a largely forgettable narrative that spans many dozens of hours.

A better example of this approach to investing in-game events with meaning is that used by the creators of Dragon Age: Origins (2009), who augmented a highly generic fantasy plot with a wealth of memorable characters who bounced off each other so effectively that one could not help but forge an emotional bond with them. I have played hundreds of video games in my life, but few moments compare to the way I felt when I decided to cheat on Zevran and impregnate Morrigan lest she leave the group prior to the game’s climactic battle. At the end of the day, my decision to betray one character in order to maintain my group’s combat efficiency was nothing but a question of mathematics — but because the writers and actors involved in Dragon Age: Origins had done such a brilliant job of making me believe in their characters, my betrayal felt like something far more unpleasant than a rational tactical choice. In fact, thinking about the decision in terms of combat effectiveness (and what that says about my character’s vision of his companions) is precisely what makes that decision so emotionally uncomfortable.

- The Sisyphean Horrors of Skyrim

Skyrim’s failure to create an emotional context for its narrative derives partly from mishandled applications of the above techniques and partly from a deliberate refusal to employ any techniques at all.

Firstly, Skyrim’s main narrative is crippled by the chicken-and-egg problem of tension and distraction. By presenting all missions as equally important, the game encourages us to spread both our emotional energies across dozens of branching narratives. In effect, this means that the main narrative is frequently interrupted for hours at a time while the players goes off and explore becoming a werewolf. Because the main narrative is presented as only one of dozens of possible tasks in your to-do list, it never has the chance to acquire the levels of dramatic tension required to sustain our interest. I say this is a chicken-and-egg problem as the game’s mission relativism is due in no small part to the fact that all of the missions are equally derivative in their nature and equally sloppy in their implementation. Presented with a generic world populated by generic characters engaged in generic activities, it is difficult to care about anything you do in Skyrim. The game’s narrative structure simply ensures that the merely difficult becomes the downright impossible. This is why people like Eric Lockaby have attempted to imbue the world of Skyrim with their own values that might provide some kind of context for their in-game actions.

Secondly, setting aside the structural problems of the game’s narrative, Skyrim’s principle narrative seems almost perfectly optimised to imbue the player with feelings of dyspeptic apathy. Oblivion (2006), the previous game in the Elder Scrolls series, complicated the traditional hero’s journey narrative by having you play not the hero but the hero’s sidekick who did all the leg work prior to the real hero stepping up and killing the bad guy. Skyrim places a similar spin on the traditional narrative by suggesting that you are only one in a long line of heroes obliged to deal with the return of dragons to the world that has served as setting for all of the Elder Scrolls games thus far. Skyrim ends with the player character visiting the afterlife in order to convince a pair of dead heroes to return and face the draconic menace that they each vanquished alone.

The cyclical nature of the draconic threat is a peculiar choice as it suggests that the role of the player is not so much to solve a problem as it is to minimise the damage caused by a recurring problem that is ultimately insoluble and destined to recur. In other words, Skyrim is the story of an innocent bystander who is forced to assume a nightmarish burden. Like Sisyphus, doomed by the gods to roll a boulder up a hill for all eternity, the game ends with the character knowing full well that he or she is doomed to spend eternity fighting the same bloody dragons over and over again. Killing bandits and collecting butterflies may not be particularly heroic or ‘epic’ but at least they have a purpose and a meaning. Skyrim’s main narrative is not so much a hero’s journey as it is a hideous mise en abyme, a portrait of bottomless futility rendered in levitating mammoths and man-eating hillsides.

Thirdly, even if we move beyond the problems posed by both Skyrim’s narrative structure and its primary plotline, we are still faced with the problem of the faceless narrator.

Much like the Metal Gear Solid, Fallout and Dragon Age series, the Elder Scrolls series is a hybrid that combines elements of the traditional computer roleplaying game with elements borrowed from both the first person shooter and the third-person sandbox game. Thus, the game takes place in the same fantastical landscape as the Baldur’s Gate and Final Fantasy series, while the gameplay is inspired by the sandbox exploration elements of the Grand Theft Auto series and the RPG/FPS hybridisation of the Deus Ex games. With so many RPGs out there, it is hardly surprising that Bethesda have tried to forge their own path by presenting their audience with a game that is mechanically quite different to those of Bethesda’s competitors. The problem is that, while the mechanics of Skyrim are the product of sustained experiment and innovation, their approach to narrative has failed to keep in step with their mechanical changes: hence the decision to build a story-focused RPG around a nameless and faceless protagonist who never reacts to anything.

The mute protagonist is hardly new to video games. Developed to suit the demands of the action genre, where the need for subjective immediacy caused designers to adopt the first-person perspective that would later form the basis of the FPS form, the mute protagonist becomes hugely problematic once games cease to be about the immediate experience of danger and become more focused upon a broader interaction with world and story.

Faced with the problem of imbuing emotional meaning to a sprawling sandbox narrative, the designers of Dragon Age: Origins opted for extended cut-scenes that provide top-down emotional context for the player’s actions. Despite being largely top-down, Dragon Age’s narrative structure afforded the player a good deal of agency in how they related to the world. Not only could the player react to the world as they saw fit, their decisions also impacted upon how characters reacted to them — and so a degree of meaning and emotional resonance was infused into what was ultimately nothing more than a series of decision trees. On a very basic level, this approach to narrative works because we see our character emoting on the screen and we take our cues from them. The same is true of games such as Grand Theft Auto IV (2008), where Niko Bellic would provide an emotional context for his actions either through cut-scenes or in-game voice-over. By refusing to give Skyrim’s character a voice and by refusing to provide a substantial top-down emotional context for his actions, the designers of Skyrim ensured that their protagonist had no emotional reaction to the world whatsoever. With no cues provided as to how they might be supposed to interpret their actions and make decisions, players float aimlessly through the world with a head full of numbers and an absolute lack of interest in the human consequences of their actions.

All games are ultimately about branching decision trees; it is just that some games are better at hiding this than others. By adopting a structure, a narrative and an approach to in-game narration that fail to provide an emotional context for the game’s content, Bethesda have produced a game whose mathematical reductionism is all too apparent. The only reason for doing anything in Skyrim is because it might improve your Damage Per Second by a couple of points. This is not so much an epic tale of heroism as it is a Randian nightmare in pre-rendered pixelated flesh; a journey through a hermeneutic and existential desert, Skyrim is the saddest and loneliest game that I have ever played.

- Chuckling at the Chasm, Babbling at the Abyss

While it should be clear that I did not enjoy Skyrim, I think many of its problems are due to the fact that much of our thinking about narrative is derived from a history and literature built up in order to make sense of comparatively short and controlled narrative journeys. Skyrim is not a novel, or a film, or a TV show; it is a small world, and if we, as a species, struggle with our place in the universe, is it any surprise that we should recreate this sense of existential detachment when we create our own digital worlds?

In many ways, the challenge posed by Skyrim’s narrative failures is the same as the one posed by the collapse of traditional cultural narratives. With God’s corpse stinking up the place and the owner’s manual for life accidentally thrown out with the VCR instructions, we live lives stripped of all inherent meaning. The emotional context of our lives derives not from meta-narratives embedded in the nature of the universe but from our capacity to latch onto the mundane details of our lives and imbue them with an emotional resonance that recreates the sense of meaning and place that our ancestors once took for granted. We enjoy telling stories and so our lives become about the quest to become a published author. We enjoy the experience of eating and so our lives become about gourmet cuisine or replicating the horrors of Man v. Food. We love our families and so our lives become all about protecting and providing for them. Life is a many varied thing and our capacity to impose meaning on our lives is nothing short of heroic. At the very heart of humanity’s spiritual being lies the capacity to render the world meaningful through the power of thought. Our ancestors used this power to embed themselves in a world of heavenly spheres and great concentric circles moved by divine love and coloured by eternal grace. We seek meaning in many faiths, creeds and identities that colour the world with narrative and warm it with context. Even those of us who struggle to find a creed worth adopting can replicate some of that feeling of meaningfulness by escaping into worlds of fiction and adventure. Of course, this raises a larger question about Skyrim.

If the purpose of escapist media is to replicate the sensation of existing in a world where our actions might have both a meaning and a purpose, why would the creators of Skyrim choose to produce a game world that is just as meaningless and futile as the real world?

While the narrative techniques at game designers’ disposals are primitive and ill-equipped for the task of imbuing entire worlds with meaning, they do at least replicate some of the techniques used by people to lend their real lives meaning. When a game designer slaps a morality system on an RPG, he is not just providing an avenue of fun or a set of mechanics to engage with, he is also providing players with the basis for decision-making. When a game designer bothers to hire decent voice actors and scriptwriters, he is not just providing players with a source of entertainment; he is also providing them with the same experience of human contact and interaction that lend meaning to our own lives.

Of course, the scientific reductionist in me wants to point out that all of these mechanics are artificial and unrealistic… but what is living a meaningful life if not a grand exercise in self-delusion? Our beliefs are carefully designed and controlled psychoses that we step into voluntarily, because the real world is just a little bit too cold, barren and dull. By choosing to not avail themselves of the techniques traditionally used to provide context for in-game actions, Bethesda have not just created a lousy game, they have fundamentally misunderstood both the purpose of video games and the nature of human existence. Frankly, ‘Fail’ doesn’t even begin to cover it.

#

Jonathan McCalmont is a freelance critic living in the UK. His work has appeared in such places as Strange Horizons, The Escapist, Salon Futura, Gestalt Mash, The New York Review of Science Fiction and Vector. He also maintains a blog named Ruthless Culture where he writes about films, literature and the fundamental hostility of the universe.

Jonathan McCalmont is a freelance critic living in the UK. His work has appeared in such places as Strange Horizons, The Escapist, Salon Futura, Gestalt Mash, The New York Review of Science Fiction and Vector. He also maintains a blog named Ruthless Culture where he writes about films, literature and the fundamental hostility of the universe.

Disclosure: I enjoy playing Skyrim.

How bleak is this review, Johnny? This review is so bleak that it completely describes how the author misses the point of Skyrim.

Skyrim is a video/computer game, of the Role-Playing Game (RPG) variety. It was designed to be the next chapter in the long-running series called Elder Scrolls.It is not a novel, film, life-changing force for good in the Universe nor does it pretend to be anything else but a game. Experienced players know what this game supplies and enjoy that enough to part with their money in order to play it. Newcomers may read numerous descriptions of this game on the ‘net in order to decide if it is for them. To expect anything else apart from the designer’s intentions is to repeat the singing pig story.

Futurismic publishes so little now; it is a shame this windmill-tilting product represents such a large portion.

“To expect anything else apart from the designer’s intentions is to repeat the singing pig story.”

Game design is now such a manpower-rich undertaking that, much like blockbuster films, intent has ceased to be all that meaningful a concept.

However, assuming (purely for the sake of argument) that the designers did indeed intend to create a world this drained of emotion, I would simply respond that their intentions were fundamentally wrong-headed. If I wanted to wander aimlessly through a wilderness devoid of structure and meaning, I’d walk to the shops.

Does this guy usually try too hard with his game reviews? Because as much as he says Skyrim is a “narrative wasteland”, his review is a diarrhea of post-collegiate diction and a delve into his misunderstanding of the excitement of open-world rpgs.

I disagree yet I completely see your point. However, walking down to the shops does not allow you to fight and shoot and fight dragons for the sheer hell and pleasure of it. Because that is what this game is. And most serious gamers rather than feel cheated by the whole feed backing loop of looting to get stronger to fight to get more loot they relish it.

Personally, I do like to be able to relate and have a context. I think that is why I swapped World of Warcraft for Lord of the Rings, there is a higher purpose in that game, but you can only be a part of it when you are strong.

The general benefit of Skyrim, and probably Bethesda intention, is to create a game with total and real free-roaming freedom, the sandbox aspect you mention.

Whilst modern RPG’s are ok and can be fun they place a lot of emphasis on general grind and levelling and can thus become monotonous. Baldur’s Gate for me had the right balance, and going even farther back, X-Com was just about perfect.

Most games have ludonarrative dissonance, but the Elder Scrolls series has it worse than most. I haven’t played Skyrim (end of semester is so close…), but I did play a fair amount of Morrowind and Oblivion, and in both cases the story of the game, about being a hero and working your way to the top of the various factions, was subsumed under the actual mechanics of the game, which was a dungeon crawler with fairly hefty encumbrance penalties. What you do, and what you’re supposed to be feeling, are about as far apart from each other as possible.

Compare this with Mass Effect 2, where you play an interstellar troubleshooter investigating the Reaper threat galaxy. The gameplay is a bog standard cover shooter, but player choice is introduced through the use of Paragon and Renegade interrupts in dialog. Shepard would invariably solve the problem, but it was up to you if he solved them as Captain Shiny or Mr. Meanface, and both choices were satisfying.

Now, ME2 is a very different type of game than Skyrim, but the point stands. Figure out what kind of ludonarrative you are–and be good at it! For me, the Elder Scrolls series has always been about exploration and faction politics, so they should make gameplay that specifically supports that. Make the process of discovering and venturing into dungeons something supported by more than the FRPG staples of balancing loot vs carrying capacity vs healing potions. Make becoming grandmaster of a guild empowering, rather than tedious.

The Elder Scrolls rules do a great job simulating a coherent fantast world, but the single most dangerous delusion game-makers can possess is their job is to accurately and completely make the the rules into some sort of “fantasy physics” rather than support fun play (unless the point is play-with-fantasy-physics, aka Minecraft).

I think a lack of emotion in Skyrim is not the core problem here. Rather, it’s that a certain kind of narrative-save the world-requires an emotional investment in that world. Emotional investments appears to require either a tightly crafted story, which is antithetical to the style of an open-world sandbox, or NPCs ‘real’ enough to prompt that investment, an intractable problem in AI.

In closing, I just want to ask: do you need a hug?

Paolo — Interesting you should make that point as an earlier version of this column proposed the idea that even when the narrative of a game fails, the simple mechanical pleasures that make up the game can still make it a winner. I would class games like Demon’s Souls in that category as both the setting and the narrative are extraordinarily (self-consciously) bleak and yet the challenge the game offers makes that bleakness not only tolerable but actually a real boon.

Part of my problem with Skyrim was that the mechanics of the game themselves were not fun. The melee was simplistic, the sneaky-archer stuff was repetitive and all about patience and the magic was dull as it was mostly about quaffing potions and mashing buttons. Had the mechanics been just a little bit more satisfying then I might never have noticed the bleakness but because the mechanics didn’t distract me, I could not get past the narrative problems.

I think the sense that good narrative is really gravy once you make the mechanics fun is why writers tend to be such lowly critters in the world of video games. If the designers do their jobs properly then the writing simply does not matter.

Skyrim is an excellent example of why this attitude to narrative can be deeply problematic.

Michael —

ME2 is an excellent example of the problem I was talking about. In essence, it’s a dull cover-shooter with some explory bits tacked onto a non-linear narrative. This kind of structure could easily have produced a game that was just as heartless as Skyrim but thanks to some decent characterisation and a morality mechanic that made you think about more than numbers, the mechanistic nature of the game passed unobserved.

And yes… I *always* need a hug!

Great post! I think there should be more game reviews like this one out there!

While I have not played Skyrim, I have played Daggerfall, Morrowind and Oblivion extensively. Despite the fact that I usually play games for their story, I never finishing the main story line of any of these! So your criticism of the Elder Scrolls’ emotional emptiness resonates strongly with me.

I guess the way I could make these games work for me is by using my imagination, in the spirit of traditional pen and paper RPGs. These games leave so much room in creating a character and exploring a world that you can add your own color to the story, and spend quite a few hours before the hollowness of quests and plot begin to make themselves felt. After that, I usually spend some time exploring the mods the community created before finally abandoing the game.

One of the most frustating aspects of the game, is that I find myself constantly fighting the game mechanics. The aspect of the newer Elder Scrolls games that appealed to me the most, was that you gain experience by using skills instead of by killing monsters. So I got it into my head to play non-combat characters who focus on brewing potions, conversation skills or sneaking. Of course the game *is* about combat, so this approach fails utterly and I spent most of my in-game time running from enemies (*especially* in Oblivion with its broken leveling mechanics).

For me, Morrowind was the high-point of the series. The diverse and alien cultures of the island made exploration fun. By contrast I found Oblivion too monotonous and stereotypical and Skyrim looks very similar in that regard. In this way, your review confirms my suspicions. Thanks!

Hi Felix —

Thanks very much for the praise.

I agree with you that the weirdness of Morrowind makes it a real highpoint of the series. One of the things that made me so annoyed with Skyrim was the fact that while its narrative structures were broken, the game gave you so little to distract you from those narratives. The combat was dull and simplistic, the setting was generic and the characters utterly flat. With so little to love, it’s little surprise that I was struck by how reductive and shallow the game could be.

This entire piece tell us something about the world of MMORPGs. Because the timeline and world you’re experiencing is linked with other players, a whole slew of tools that could be used to build dramatic tension and imbue your character’s actions with meaning are lost. You can’t freeze time or substantially alter the environment lest everyone around you experience that, or some other conceit is used where you effectively vanish from the world.

However, tension is created through the knowledge you’re interacting with other *real people*. I might be more likely to stage a raid on an enemy village if I cobble together a team of other players to help me do that. This doesn’t advance any kind of narrative but it really is a form of virtual cowboys and indians we’re hardwired to enjoy.

Unfortunately for MMOs, the bread of fun experiences like this all has to be made by you manually operating the grindstone. “Travel to the kingdom of Snoretopia, where an evil witch has sequestered our villages’ two Golden Penguins that bring us good luck. Return the penguins to us and there shall be a fine reward for you!”

Players put up a lot of this stuff because pushing the feeding lever to dispense the pellets of weapon upgrades enables you to enact your cowboy and indian stories more effectively. So what if you made a game where you pushed the pellet, got the weapon upgrade, but you had nobody else to play with? That game appears to be Skyrim.

Recently I’ve been on a major Dark Souls bender, but I decided to continue that post on my blog instead to avoid infecting people here: http://hagus.net/?p=81

Thanks for this article Jonathan, it was really great!

“deep and complex”? Granted, I’m still working on Elder Scrolls IV, but the verdict applies to that game as well. Stunning visuals, quests from here to Tokyo, but you can’t take the throne yourself by murder and deceit. In the absence of a king, one would (in the real world) expect nobles to start scheming. It’s like a sphere à la Sloterdijk, very much like a spaceship, where every assumption is worth considering. There are tons of things that make the Elder Scrolls-series go tick, keep it alive, but rapidly prove shallow, to say the very least.

For example, I like to play RPG’s as a hack ‘n slash female (I’m male). Such women have, I think, a unique psychology. In general Buffy and Xena seem to be the exception, not the rule. But NPC’s do not respond to that. Also, there are no complaints about the weather (among British and Dutch this would be topic no. 1). Are these characters real people? They have no opinions, they don’t age; they look more like aliens.

Having said all that, it’s not going to stop me from playing Oblivion & Skyrim…

I have played Morrowind Oblivion and Skyrim in depth. However I feel that it is not the narrative that drives these games at all, instead it is the effect of choices and consequences of the individual player that determine what will or should happen next. In Morrowind the world was large and the multitude of choices made it difficult to predict the results of your actions. This led to a unique story that appealed to many simply because it was so variable. Oblivion simplified the choices by allowing fast travel, removing skills found “redundant” or “undesirable” and by introducing the idea that a game like this can be made for the PC, Xbox, and other consoles collectively. While the graphics of Oblivion were a vast improvement over Morrowind the simplification resulted in a decrease in the variability of gameplay. This decrease in variability resulted in the experience of a linear narrative where none had existed before. Unfortunately Skyrim as followed this pattern of improving graphics and appealing to beginning gamers while removing many of the appealing traits that started this genre. The unique situations where the character could make choices that affected every consecutive outcome disappeared with this newest installment and in return we were given dragons to slay while our magic selection, skills, interactions with guilds, and realistic experience of choices and consequences dwindled. Not a trade that I feel is fair.

What I like most about Skyrim and the other Elder Scrolls games is what they don’t have : a mandatory save-the-world storyline, complex relationships with companions, cinematic cutscenes.

Few things annoy me more in a RPG than being unable to take my time, explore and look around, because the kingdom/the world is in urgent need of saving. Or game designers who believe that dialogue, cinematics and game mechanics can somehow make me relate intimately with their fictional characters as if they were real people.

I prefer RPGs that are about my character’s fate, not the world’s. When I play, I like to imagine my character’s own goals and feelings and organise his or her priorities accordingly. But games like Dragon Age (A sandbox narrative ? Seriously ? It’s as linear as they come) or ME2 seriously interfere with my ability to do just that : the priority is to save mankind, and my character’s personality has to be expressed through predetermined “choices” along the way. Gah.

That’s why I find it relieving and refreshing to find a modern RPG like Skyrim that still refuses to use the “techniques” listed in this article.

I’m not completely happy with Skyrim, though : while the main quest is optional, it’s still about saving the world, which can cause some awkwardness (like that dragon who obligingly waited for me to complete my Grand Tour of Skyrim before it decided to attack Whiterun).

And it could certainly use some improvements to make it feel less shallow, like more secrets to uncover, or interesting ways to use all the wealth, knowledge and power you’ve gained. Still, I’m glad this game exists.

**Content-free comment deleted! Feel free to return when you have an argument to back up the beef, yeah?** – Ed.

Meaning in Skyrim needs to come from the player – in creating a character in his head and playing that character. The voiceless protagonist is critical for this – to hear your own voice for the character in your head, rather than the voice actor’s.

To embellish on Brian’s point:

Reading this essay got me thinking about the Elder Scrolls franchise, and in particular a design note made in the manual to Daggerfall. I don’t have the manual at hand, but I remember the focus was on letting the player ‘write their own story’ and tell it how they want.

That’s particularly clear in Daggerfall, since the content provided by the game was a bit bland, and the randomly-generated citizen of the world didn’t exactly pass my Turing gut-test. That said, with that ‘tell your own story’ mandate, it allowed me, like a theatre improviser, to take what I’m being given and work with it, develop it into a narrative that I find interesting..

Most of the main Elder Scrolls games have all operated in this fashion, so I wonder if critizing them because of it might be working against the grain of the game.

To quote you: “By refusing to give Skyrim’s character a voice and by refusing to provide a substantial top-down emotional context for his actions, the designers of Skyrim ensured that their protagonist had no emotional reaction to the world whatsoever.”

I’d argue that Skyrim isn’t failing to provide you an emotional context, so much as it’s asking you to bring one. (Ditto for the Elder Scrolls in general.)

A personal anecdote:

A friend and I play Skyrim together, and change characters when we change who’s handling the controller. What we often find is a vastly different playing experience. (I tend to be more Paladin-esque, whereas he’s more of an assasin/theif-type player.) We’ll approach the same dungeon/keep/quest/conversation in different ways, and be telling different stories within the game. We’re often showing each other something that the other handn’t discovered in their own playing style.

I’d argue that we’re bringing our own investment and filling a void intentionally left for the designers, and that doing so creates an involved playing experience, different from ones where the narrative is pre-packaged, or forked into a few different narrative tones. (Which isn’t to say those aren’t fun as well, just different styles.)

Thank you, Jason Mehmel, for pointing out the designer’s note from Daggerfall.

It’s important to realize that not all games serve one purpose. The Elder Scroll writers haven’t failed to understand “the purpose of video games”, they’ve adopted a distinct one. The intention is not to tell you a story, but to give you tools to write your own. The game won’t care for you, and some players prefer it that way. Of course, there are also players that will miss this entirely (those just in it to win it, and completionists, mostly).

I honestly think they just shove in a main quest to placate those who don’t get it, and if they fail, they fail. The rest of us don’t need it.

While each element of the game design’s quality can be debated ad nauseum, I think the whole package suffices.

Sounds like you’re questing for meaning in the wrong place… YYYEEEEAAAAAAAHHH!!!!

All very nicely reasoned, and I do agree that Skyrim’s story-telling has only gotten more confused compared with Oblivion (in exchange for the significant graphical and combat system improvements), however, I don’t understand the mention of the cylindrical dragon problem?

Alduin only returns in Skyrim because he wasn’t properly defeated the first time. The events of Skyrim result in Alduin’s final destruction. Sure, the dragons don’t disappear afterwards like the Oblivion gates did, but they are no longer organised under a single tyrant, and (depending on your choices) may even have the potential for a peaceful group to emerge in time.

Anyway, I do agree overall that Skyrim’s story telling lacks focus, and the sheer quantity of mundane quests that you can accumulate is simply staggering, and you’re essentially forced to spend hours clearing them away before you can focus on important things again, or learn how to refuse quests (not always that easy).

My other main gripe is that the various guilds in Skyrim don’t have any real impact on events at all; I’d been hoping that gathering allies would be a key part of the game, but instead we have the same tired formula from Oblivion where a character with any skill-set waltzes into a guild, does a lot of graphically pleasing, but largely hollow, quests, and ends up in charge of the guild. There’s no character to any of the guild-quests really; where are the guilds that aren’t facing some huge calamity? Where is the choice in many of them, most are very linear! The big hook (and big difficulty) with Skyrim is making the story your own, with your own character, and your own choices, but we still don’t get much of that.

A good example is the College of Winterhold. The questline for it is a fairly boring calamity about some ultimate magical power, that leaves the arch-mage dead and for some reason you’re the best qualified to take his place, even if (like my character) you’re an evil assassin with no real magical talent at all. Instead, they could easily have explored the destruction of Winterhold; found out who was really responsible, and possibly start quests to rebuild, all through a more personal story of what was lost and why. Leave the arch-mage part up to some genuine magical trials that require you to have some skill in, oh I dunno, magic?

In short. I disagree with basically everything you said.if you dont have the mental capacity to understand a complex story, and arent willing to google things you dont understand, iv got one tip for you. Dont play it, or write a review that ultimatly spoils it for anyone looking to buy it.

Thank you. I don’t entirely agree with your assessment of Skyrim but much of what you wrote is very similar to my feelings. I’ve been trying to express my disillusionment with most video games, not just RPG’s, and this article did a fair bit to quantify what I have left unexpressed. You can take your entire article and apply it to almost any current genre of video games. I think we were introduced to video games as children (even if some of us were supposedly adults), came to be enamored with their flashy pictures, stiff music and varied button pressing skill sets. What we desire as we mature to video games, not necessarily in age but in consumption, we want more and more from these games. To go a little biblical, as a child I played like a child, as an adult I set aside childish things. I don’t consider video games themselves to be childish, but the notion that they can’t provide you some type of emotional feedback is.

Arguments for a sandbox or open world game make sense but no video game has ever or probably will ever establish an open world or sandbox game, despite their attempts to define themselves as such. You can’t go into Skyrim and become a merchant, that is a limit on the game. Regardless of how free you can roam, you can’t explore beyond the farthest passes, which means you have a somewhat geographical and linear limit as many areas are only traversable by movement limiting pathways. Yes you can choose when to attempt an objective, or you can even avoid objectives altogether, but the moment you do, the game becomes a series of hack and slash events, and will eventually become boring. There are only so many woolly mammoths you can kill before the fun and danger of doing so is overwhelmed by your developing methods to ensure safety and success.

As I read this article it put into perspective all the reasons I have slowly weaned myself from video games and now just play them for their silliness and not any deeper complexity. I like Skyrim because it’s pretty, I can shoot things that are difficult to shoot and I can kill dragons with a lot of effort. Plus I like shouting things off mountain sides. An hour of that after a stress filled week is a great time killer, but eventually I turn off the computer because the game does not require much emotional input. if I wanted to create emotional input, as suggested by someone, why would I choose a video game? I could go meet friends for drinks, much more emotionally invested.

While I disagree with most of your sub-points, I think it most important to confront your main argument against/ issue with the game: that it doesn’t provide an emotional experience to the user. You failed to recognize a third approach to “emotizing” a game experience that is gaining traction in recent franchises (namely, Bethesda’s games and the Mass Effect series– there are probably more but those are the ones I’ve played). This approach seeks to place the player in positions of moral choice that have repercussions in the game world. E.g. in Skyrim you can choose to side with the Empire or the Resistance. Most players will probably be drawn towards the resistance, but that faction clearly has racist underpinnings designed to steer you away from it.

Another great example I faced late in the game was whether to kill Paarthunax, a reformed dragon who helps you in the main quest, who has in his backstory the murder of countless humans. The Blades (a faction) want to see him dead, and demand that his reformation is meaningless without his answering for his past actions, and you can only complete the Blades faction after killing him, but doing so will cut you off from another group in the game, the Greybeards.

I played the game with my main motivations in making game-world choices (1) that I thought the game world was beautiful and wonderfully created (I was stunned the first time I saw Solitude standing on the giant rock-arch), and thus wanted to explore it and (2) that because I found the game world idyllic, though still plagued by complexities, and I wanted to preserve and defend that with my game-world actions. I acted in the game world as I would in the real world, and the narrative is designed to non-judgementally allow you to impress your moral person on the experience. So I’d say that your claim that the entire reason a player would make a choice is based entirely on trying to level their character misses the mark. For my gaming dollar, Skyrim represents a well-realized vision of this approach. It presents its story with nuance and cleverness, not to mention a level of allegory, that is rare.