At times of crisis, the irrationality of capitalism becomes plain for all to see. Surplus capital and surplus labour exist side by side with seemingly no way to put them back together in the midst of immense human suffering and unmet needs. In the midsummer of 2009 one third of the capital equipment in the United States stood idle, while some 17 per cent of the workforce were either unemployed, enforced part-timers or ‘discouraged’ workers. What could be more irrational than that? – David Harvey The Enigma of Capital (2010)

In my previous column, I cast an eye over the different ways in which strategy games depict the world and how these distorted visions of reality mirror the distortions that affect people when they become part of large institutions, such as governments and corporations. In that column, I discussed strategy games such as Civilization V (2010) and Europa Universalis III (2007) and god games such as Populous (1989) but I omitted to mention games that set out the simulate what it is like to run a business.

While elements of the business simulation game can be detected in a number of games from a wide array of different genres including the life simulation of The Sims 2 (2004) and the crime epic of The Godfather (2007), titles such as the Railroad Tycoon and Theme Park series as well as individual standouts including Ports of Call (1986) and M.U.L.E. (1983) attempt to capture the essence of the capitalist experience in a far more purified form.

Much like the rest of the strategy genre, business simulation games are ultimately about engaging with a model of political economy. As a player, you are presented with investment opportunities and, depending upon both your luck and your skill, these investments will result in profits that can then be farmed back into larger and more ambitious investment vehicles as you grow your business empire.

However, what is most noticeable about these business simulation games is that, regardless of how closely they may or may not mirror the economics of the real world, they all make sense. They all present capitalism as a rational system that can be successfully gamed and effectively ‘beaten’. But is this not a rather large assumption to make about the nature of capitalism? After all, if recent events prove anything it is that the financial system is profoundly irrational. Two recently released browser games have responded to the credit crunch by using different techniques to demonstrate both the irrationality and injustice of contemporary capitalism. This column celebrates their critical gaze.

1: Pointing and Laughing

Developed by Increpare, Terry Cavanagh, Jasper Byrne and Tom Morgan-Jones American Dream follows Christine Love’s Digital: A Love Story in aping the visual style of period video games to help ‘set’ the game in a particular period. In this case it is the primary colours and crude graphics of the ZX Spectrum and the setting is the 1980s of Oliver Stone’s film Wall Street (1987).

You begin the game with an empty apartment, enough money to make an initial investment and a dream of making a million dollars within a year. You begin work as a stock broker but rather than buying and selling shares in companies, you find yourself buying and selling shares in period celebrities such as Mr T, Michael Jackson, Blondie and Bill Cosby.

This situates American Dream well and truly within the arena of the satirical. Aside from being fiercely reminiscent of the BBC’s celebrity stock exchange game Celebdaq, the reduction of the stock exchange to the buying and selling of personalities also constitutes a neat criticism of the business world’s fondness for personality cults. Indeed, when people buy shares in Apple computers, are they looking at the performance of the company and their tiny market share of the home computer business, or are they simply allowing themselves to be bamboozled by that nice Mr Jobs?

Perhaps the best-known popular account of the credit crunch is Andrew Ross Sorkin’s Too Big To Fail – Inside the Battle to Save Wall Street (2009). Nominated for the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction, Too Big To Fail describes what happened when the bubble finally burst and the merchant banks began to tumble. Aside from being an insightful and well-written book, Too Big to Fail benefits hugely from Sorkin’s decision to focus upon the personalities behind the credit crunch rather than the economic theory. Indeed, the opening of the book reads like the opening to a 19th century French novel:

“Standing in the kitchen of his Park Avenue apartment, Jamie Dimion poured himself a cup of coffee, hoping it might ease his headache. He was recovering from a slight hangover, but his head really hurt for a different reason: he knew too much.”

In Writing Degree Zero (1953), Roland Barthes bemoans the fact that all 19th Century French novels seem to open with this sort of past tense narration. Barthes explains that when novelists write about how the Marquise went out at five, they are describing an action that is “closed, definite, substantive”. This means that the act is resolved and subject both to human comprehension and description. There is comfort to be had in the idea that our actions can be so pithily described and that comfort only grows when the actions become as vast and complex as those involved in both the creation and puncturing of the credit crunch’s financial bubble. We struggle to make sense of the economic forces governing our lives and so we choose to focus upon the personalities and the human faces of the institutions involved. By reducing the stock market to an absurd celebrity popularity contest, American Dream is reminding us of how ridiculous and irrational the financial markets really are.

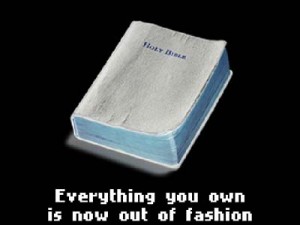

The second element of American Dream’s gameplay involves purchasing consumer goods. Seeming to lack any intrinsic value, the acquisition of these objects constitutes something of a justification for working and accumulating money. In the world of American Dream, you never need to bother about buying food or making rent, but you do have to make sure that you have all the latest consumer goods… and, every so often, a new catalogue comes out, forcing you to throw out all of your worldly possessions and start again from scratch. As in David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), the relationship between the burdens of work and the demands of consumerism form an absurdly closed circle; you work in order to buy stuff and, because you want to buy stuff, you keep working. The character in American Dream has no inner life or hobbies; he simply buys stuff, and so helps to keep the consumerist treadmill moving – even though he could step off it at any point.

When you manage to buy everything that it is possible to buy, you are rewarded with a party that rapidly descends into an orgy of drugs and sex. At these parties you will pick up tips on which stocks are about to go through the roof and these tips are never wrong. This section of the game is both trenchant and double-edged as, on the one hand, it points out the extent to which our desires are socially determined (no fashionable consumer goods = no social life) and, on the other hand, it points out the artificiality of the financial system. Indeed, by having you buy shares in celebrities that go up and down seemingly at random, the game is not only commenting on the fact that stock prices no longer seem to bear any relationship to the objective health or value of the businesses they represent, but also on the fact that the movements of the market are determined by the actions of a global elite. People talk up shares at parties in between lines of coke, and companies are worth more. People talk down shares at parties in between hookers, and hundreds of people lose their jobs as share prices tumble.

By satirising the worst elements of 1980s excess, American Dream reminds us that the system we are a part of is neither just nor rational and that those who benefit from it are far more likely to be lucky or corrupt than smart or hard-working. The injustices and harshness of American society are displayed in an entirely different manner by the second game I want to discuss.

2: Lamenting and Hand-Wringing

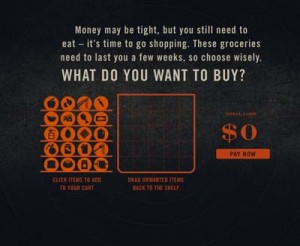

Developed by the housing charity Urban Ministries of Durham in association with an advertising agency, SPENT assigns you the challenge of making it through a month as an unemployed American single parent. Designed to educate as well as entertain, the game presents you with a series of daily choices and dilemmas ranging from whether to pay for your child to attend a museum through to how close you should live to work and whether or not you should opt in to health insurance plans and try to join a union. Each decision you make has a financial cost, and even if you make the right decision the game reminds you that you lucked out this time, that next time it could be worse and that millions of people in your situation make the wrong decision every single day.

Much like American Dream, SPENT presents the capitalist system as an inscrutable black box; in American Dream you never learn what makes the prices of celebrity stocks go up and down and in SPENT you never know whether or not you will be made redundant, fall ill or be forced to assume some unexpected financial responsibility. In American Dream, the system seems unjust and absurd because you do not know what you are doing and you make a fortune, but in SPENT the system seems unjust and absurd because you can make all the right and rational moves and still wind up broke and unemployed with a child to look after. In many ways, Spent plays like an updated version of Oregon Trail (1971) but with a contemporary setting.

Part of what makes SPENT so powerful is its refusal to limit itself to the bottom line. For example, throughout the game you will be asked to give money to something that will in no way help you to pay the bills and make it through the month; do you buy your kid an ice cream? Do you help out your work mate by pitching in when the hat is passed round to help him pay his medical bills? Do you pay several hundred dollars to fly to your best friend’s wedding? While it is easy enough to make these choices with the game’s logic in mind, each time you are called upon to make these choices, you are reminded that there is more to life than simply surviving and paying the bills. $10 can be a lot of money if you are close to the poverty line… but is that $10 not well spent if it brightens up your child’s day even a tiny bit?

American Dream and Spent borrow game-play elements from the business simulation genre in order to subvert the central assumption underpinning the entire genre, namely that capitalism is rational system at which it is possible to ‘win’ if you are sufficiently skilled and sufficiently motivated. However, while both games are ultimately concerned with critiquing capitalism, they set about their task in very different manners as SPENT attempts to model the real injustices and difficulties of life in America while American Dream presents American capitalism as a grotesque fantasy in which people throw money at celebrities, take a load of drugs, buy $1,000 kettles and somehow get rich in the process.

Civilization V and Europa Universalis III are strategy games based upon an abstracted model of the real world and because that abstract model is based upon the state’s eye view of the world, both games make individuals disappear and so make it easy for players to commit atrocities. However, both SPENT and American Dream are also strategy games that are based upon an abstracted model of reality but, far from making individuals disappear, these games instead draw our attention to the real human cost of the empires built by western capitalism. The question is, would it be possible to combine the complexity of a Civ V with the satirical intent of an American Dream or the educational intent of a SPENT to create a business simulation that is more than just a vehicle for psychopathic fantasies of agency? Could a strategy game reveal to us the true nature of capitalism?

###

Jonathan McCalmont is a freelance critic living in the UK. His work has appeared in such places as Strange Horizons, The Escapist, Salon Futura, Gestalt Mash, The New York Review of Science Fiction and Vector. He also maintains a blog named Ruthless Culture where he writes about films, literature and the fundamental hostility of the universe.

Jonathan McCalmont is a freelance critic living in the UK. His work has appeared in such places as Strange Horizons, The Escapist, Salon Futura, Gestalt Mash, The New York Review of Science Fiction and Vector. He also maintains a blog named Ruthless Culture where he writes about films, literature and the fundamental hostility of the universe.